The Myth: Tattoos, while part of many indigenous cultures, had faded from memory in Europe until the 17th century voyages of Captain James Cook. Cook and his crew encountered tattooing in Tahiti and throughout the Pacific Islands and New Zealand. In reality, tattoos are part of most indigenous cultures dating back centuries. Perhaps most striking are the elaborate marks on the body of a high-ranking woman found in the Altai Republic.

Elegant even in decay, her body art is striking even after 2,500 years in the ice. Discovered in a stone tomb on the Siberian Ukok plateau, she is believed to be a member of the Pazyryk people, a nomadic group described in the 5th century BC by Greek historian Herodotus. She had a headdress 3-feet high that required the coffin to be 8 feet tall and is thought to have been a priestess or medicine person in her community. She had breast cancer, had probably fallen from a horse and probably used cannabis to manage her pain. Here is a sketch of the deer-related creature on her shoulder.

Tattooing as part of religious pilgrimage dates back to the 14th century in, particularly in Coptic and Eastern Christian traditions. A small cross on the inside of the wrist would grant entry to churches and other Travel records from 1602 show that the Persian and Arabic guides of the Franciscan friars in the holy land created tattoo stencils from wooden blocks. This tradition persists to the present day.

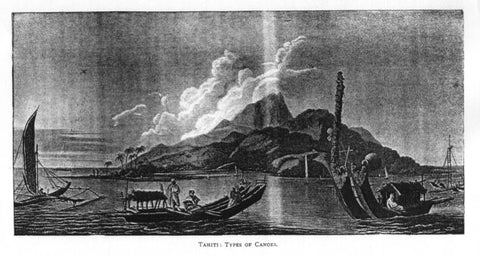

Like pilgrim tattoos, sailor body art is often used to chronicle journeys both physical and otherwise. The exploring tendrils of Europe stretched out on sails and wood, expanding the known world. Captain James Cook first encountered tattoos on the native Tahitians and throughout the Pacific Islands and New Zealand. Some of Cook's men were themselves tattooed, as told in an excerpt from Endeavor crew member, Sydney Parkinson:

"Mr Stainsby, myself, and some others of our company, underwent the operation, and had our arms marked.”

- Sydney Parkinson’s Journal , 13th July 1769