We also had a close call with the CZU August Fire at my brother's house, my childhood home, but have been lucky. I went to college at UC Santa Cruz, spent childhood summers camping in Pescadero and Big Basin and a myriad memories scattered in those mountains.

Yet California needs fire. Fire is part of this place. Fire and other land management techniques are part of a healthy California ecosystem. The hours I spent researching ethnobotanist Kat Anderson's work at UCLA's American Indian Studies Center on native Californian landscape management were many. This brings me to baskets and fire.

The majestic and profoundly sophisticated baskets made by Native Californians are possible because of management techniques that resulted in heathy patches of bear grass, deer grass and usable shoots on hazel bushes that were right for basket weaving. Fire broke the disease cycles of filbert worms and acorn pests while stimulating a healthy crop. Controlled burns after the mid fall acorn harvest also cleared out overly crowded seedling growth that supported a distribution of large healthy trees of different ages. Without intervention, the oak pests can decimate 95% of the annual acorn crop. (Quick note - John Muir noted that Yosemite looked like a park with scenic views and winding open meadows. The expulsion of the local indigenous communities and their millennia-old land management practices were also the end of Yosemite Valley as it had been for centuries. The last native village in Yosemite Valley was bulldozed to make way for campsites in 1969.) The delegitimization of traditional ecological knowledge has contributed in nearly two centuries of fire suppression.

It is estimated that 350,000 people lived in California in 80 language groups at the time the Europeans arrived. In The Fine Art of California Indian Basketry, basketry scholar Bruce Bernstein shared that "Baskets were integral to the activities that were the foundations of life - infants were carried in baskets, meals were prepared in baskets, and baskets were given to mark an individual's entrance into and exit from this world." The impact of displacement and genocide by Euro-American settlers and the degradation of the ecosystems since the Gold-Rush has decimated Native basket traditions and their maker communities. After European settlers disrupted existing ecosystems and economies, indigenous women were able to for the tourist market between 1890 and the late 1930s, Thanks to a small group of weavers in the 1960s and 1970s, these traditions were passed on to a handful of weavers. Only about fifty baskets are known to date before the gold-rush era.

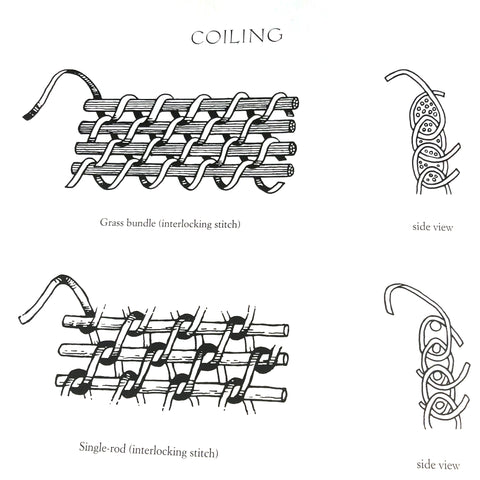

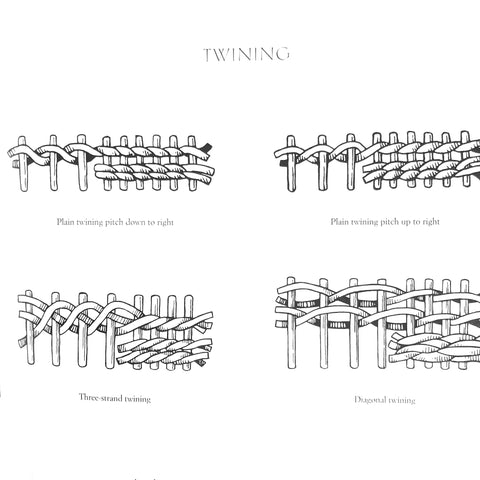

Californian native baskets are among the finest in the world, arising from a 6,000 year tradition and the right climate for a myriad weaving supplies. Baskets were created for function and ceremony - with purpose expressed through their design. The technologies involved in making baskets included six twining techniques, three coiling techniques as well as wicker work in some areas. Coiling appeared about 3,000 years ago and established itself as the primary technology in two thirds of the state. The northern third of the region used only the twining techniques.

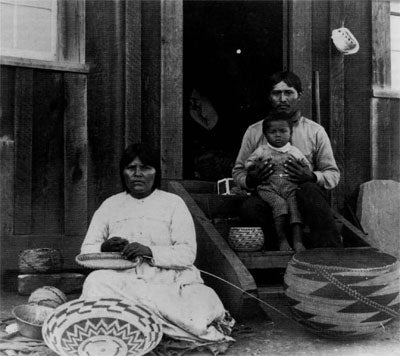

Here is well-known basket weaver Joseppa Dick with her husband, Jeff Dick, and son Billy, Yokayo Rancheria. (Photograph by H.W. Henshaw, ca. 1892. Courtesy of Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, Cal.)

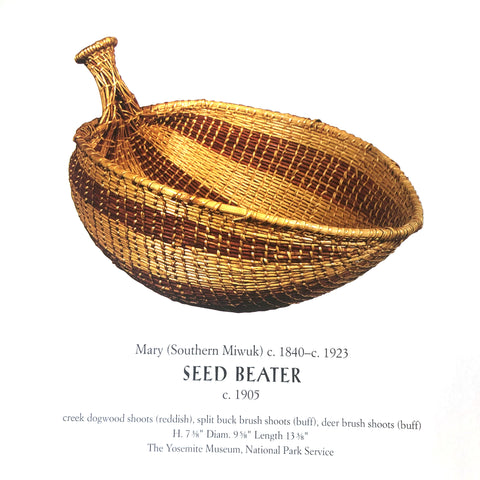

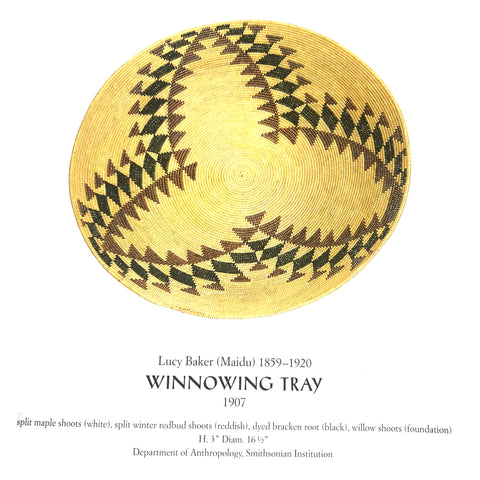

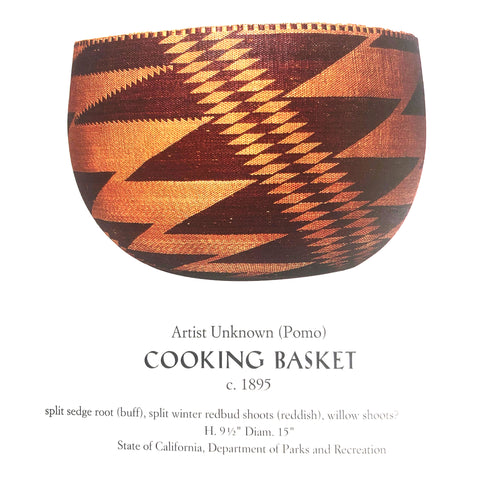

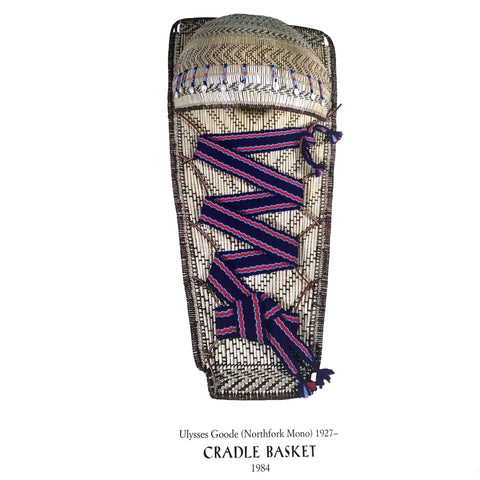

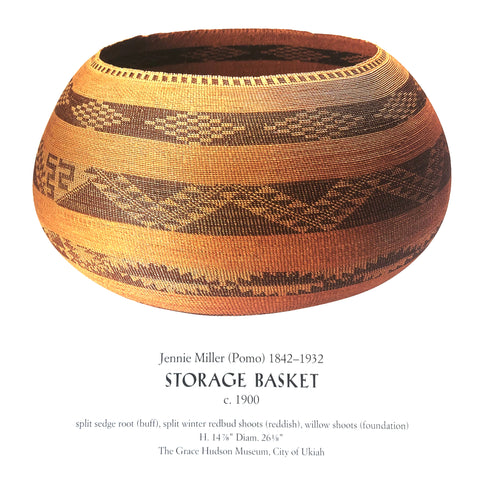

Some of the central categories of California baskets are burden (carrying) baskets; seed beaters, hoppers and winnowers; storage baskets; cooking, soup and feasting baskets; caps, cradles, ceremonial and gift baskets. There is remarkable diversity within Californian basketry traditions. The shape, design, materials and weaving technique of a basket with a similar function varied based on the traditions of the community.

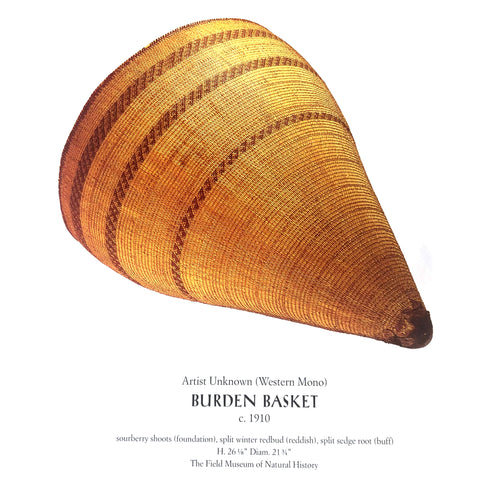

Acorns played an important part in many local foodways. There are up to eight different baskets involved in the harvesting, carrying, storage, processing, cooking and eating of acorns. Think of the great resilience and durability of a water tight cooking basket that can withstand boiling acorn mush and hot stones from the fire. Large burden baskets were often made with willow shoots or sourberry shoots as the foundation. They were made with wide mouths for easy seed harvesting and to carry greens, bulbs, acorns or other foods. They were carried with a woven tumpline (strap that goes over the head), as seen in this Edward Curtis photo of a Pomo woman carrying a burden basket.

In 2015, this 200 year old Chumash storage basket - the largest known, was discovered in a cave cache in the Santa Barbara backcountry. It is now at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Tradition is alive and native people of what is now California still exist. Learn more or support current weavers through the California Indian Basketweavers' Association.

Here is a short video of Julia Parker of the Kashiwas Pomo and Coastal Miwok Bands talking about basketry and showing her gambling tray from grasses and redbud, which took her four months to make. Her work is in the Smithsonian and she worked for years demonstrating basketry in Yosemite. Large baskets could take more than a year from harvesting and preparing materials to completion. For Redbud, the weavers were instructed to wait until after the leaves turn yellow and fall off. Then wait for the first frost to make the long slender stalks easy to harvest. But still - wait for the first rain to see the color of the redbud, since the color of the redwood is affected by the soil in which it grows, for example an iron rich soil would produce a more red color.